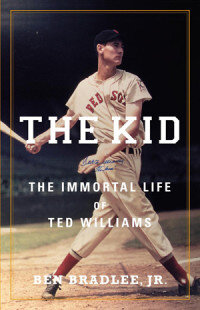

The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams

by Ben Bradlee, Jr.

Little Brown (2013)

Everything we wanted to know about Ted Williams and more?

At first blush yes, hell yes! After all this is the umpteenth book written about Williams, a 775 page tome that if dropped on the scales would outweigh one of The Kid’s Louisville Sluggers, the lumber that the Splendid Splinter spent a career baking, boning, primping, until they—in the hands of that incredible swing of his—made him the greatest left-handed power hitter to ever play the game.

But thanks to this Ben Bradlee, Jr. biography, what we have is: EVERYTHING we wanted to know about Ted Williams.

Ted Williams was half Mexican. Ted Williams made a career of not only knocking down American league fences he carried a lifelong chip on his broad shoulders the size of one of those satin Pedro’s South of the Border pillows. And, says Bradlee, this can be traced back to the kid’s shame of his Mexican background and his upbringing by a single mother who spent more time on the streets of San Diego banging a tambourine for the Salvation Army than she did at home raising Ted and his younger brother.

Once we’ve learned that his mother was Mexican and how it impacted Williams’ personality, did Bradlee need to shake the kid’s family tree until reprobate uncles and alcoholic aunts came tumbling out? Perhaps not. Are there a few too many graphic details about the cryptogenics and where the man’s head hangs today? For this reader, yes.

But there is little not to like about this most comprehensive biography and in the end it confirmed that the very complex (probably bi-polar)personality of Ted’s could change directions as fast as a Fenway fair pole flag, from to as sweet as his swing to as sour as the bile he expectorated at the Boston press box.

Ashamed of this mother but loved her to his dying day. Hated sports writers whom he called “the knights of the keyboard” but secretly slipped them cash when they were down and out. A blasphemous self proclaimed atheist he would eventually publically reach out to God. He could be nasty to his own kids and yet incredibly nice to others, with a positive focus on the sick and dying (The Jimmy Fund).

And as his story unfolds it’s these ill fitting pieces of this persona that make the 700 plus pages read more like three hundred. A great deal of this can also be attributed to Bradlee’s copious research with examples a plenty including detailed accounts of his fight against the draft boards in an attempt to dodge WWII and Korea (this was more about money and the loss of playing time and big contracts than what the public perceived as cowardice) and then, ironically as a Marine bomber pilot how heroically he fought those wars he so desperately tried to dodge—right down to the detailed story of Williams’ crash landing after being winged by enemy fire over Korea.

A very smart cookie in the lexicon of his day and Bradlee feeds us numerous anecdotes that showcase Williams the incredibly talented perfectionist—hitting, pitching, fishing, photography; anything he touched had to be done right. When it wasn’t he exploded like one of those bombs he dropped in North Korea. And baseball purists who crave the game’s numbers won’t be disappointed. The Williams’ stats and records are all here to be scrutinized. So prepare to be impressed. Just compare and contrast.

But as we peel the onion under that Red Sox cap of his, it makes a reader pause. How could this accomplished womanizer (he got hotter than his bat in his 30s and kept it swinging most of his life), a man who could be so crude, foul mouthed and misogynic, (he missed the birth of his first child because he was “busy” fishing in the Florida Keys) be so generous with his time and wealth, so compassionate that (again) he’d never refuse a visit to a hospitalized kid (unless the press got wind of it and were planning to alert the public to Williams’ acts of kindness). Yet this man who accumulated 2,654 career hits clearly missed as a father, begetting two daughters (one with major personal issues) and a son (John Henry), who he loved dearly, but in the end would rob his father of both cash and dignity.

Like many great athletes who’ve competed for the spotlight (Mickey, Willie and the Duke) Williams vs. DiMaggio became an American obsession. Save WWII, they were the water cooler topic of the day. In ‘41 DiMaggio ran off a 56-game hitting streak. The Kid capped off that historic season by hitting over .400. “The Dago’s the best all-round ballplayer!” said Yankee fans. “Ted’s the betta hitta!” countered Beantowners.

On this subject we hear from teammates, friends, family, and confidants. Then, in Bradlee captured quotes, the two players weigh in. Williams always gave Joe high praise, calling him the “best ballplayer who ever lived.” Conversely DiMaggio, who could be quite petty, publically dished out “left-handed” compliments regarding the Splendid Splinter (“Williams is the best left-handed hitter”). But privately, to friends, he never gave The Kid his due (“a good left-handed hitter but a weak arm and not a complete player.”).

Perception being reality DiMaggio was the picture of class, Williams the uncut gem. And Williams was okay with this.

On a hot summer day in the late ‘50s, after his final swings at the plate, Williams took a late inning early exit from a meaningless game in Washington, DC’s Griffith Stadium. With my dad on my heels, I did the same, heading to the visiting team’s locker room. I wanted to be there when Ted walked out. When the green door opened out came the best left-handed hitter to ever play. Handsome as hell, he wore gray slacks, a blue blazer and a white open necked shirt and I, alone, (save my dad who stayed back) walked under the stadium’s old girders toward the street in the shadow of greatness, trailing the famous Ted Williams. As I chatted him up on his way to a cab stand he said very little, nodding several times when he stopped to sign my baseball. Then a man appeared and asked if he’d sign his scorecard for his son. Williams said, “Bring your son along to the game next time and I’ll sign for him!”

As I watched his cab pull into traffic I was left with an autographed ball and the memory of my moment with the American icon. More than half a century has passed now and there’s not a baseball fan in the world who doesn’t know that Ted Williams could hit. But what struck me personally about The Kid, Mr. Bradlee’s excellent biography, was for all the author uncovered in this well excavated dig into Williams’ DNA (the great, the bad and the ugly)—Mr. Bradlee reinforced something I’ll never forget.

The Kid was good to this kid!

For a copy of The Kid, ask your librarian, order as a Christmas gift through your independent bookseller or try Amazon.com where you can buy the 2013 novel for less than The Kid paid his butcher for those bones he used to hone his bats. Simply click on the book’s cover.